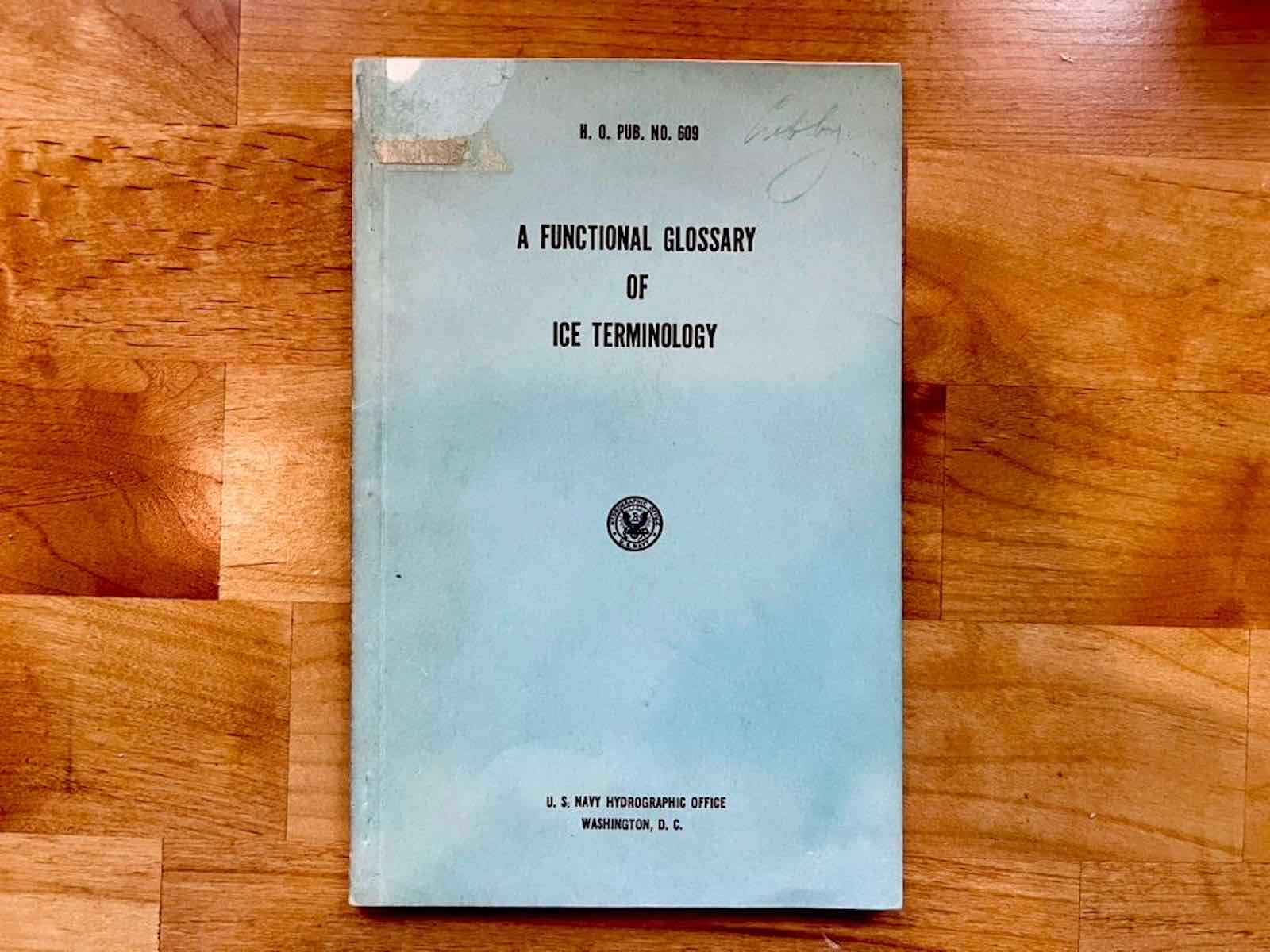

What was the first book you bought for your collection?

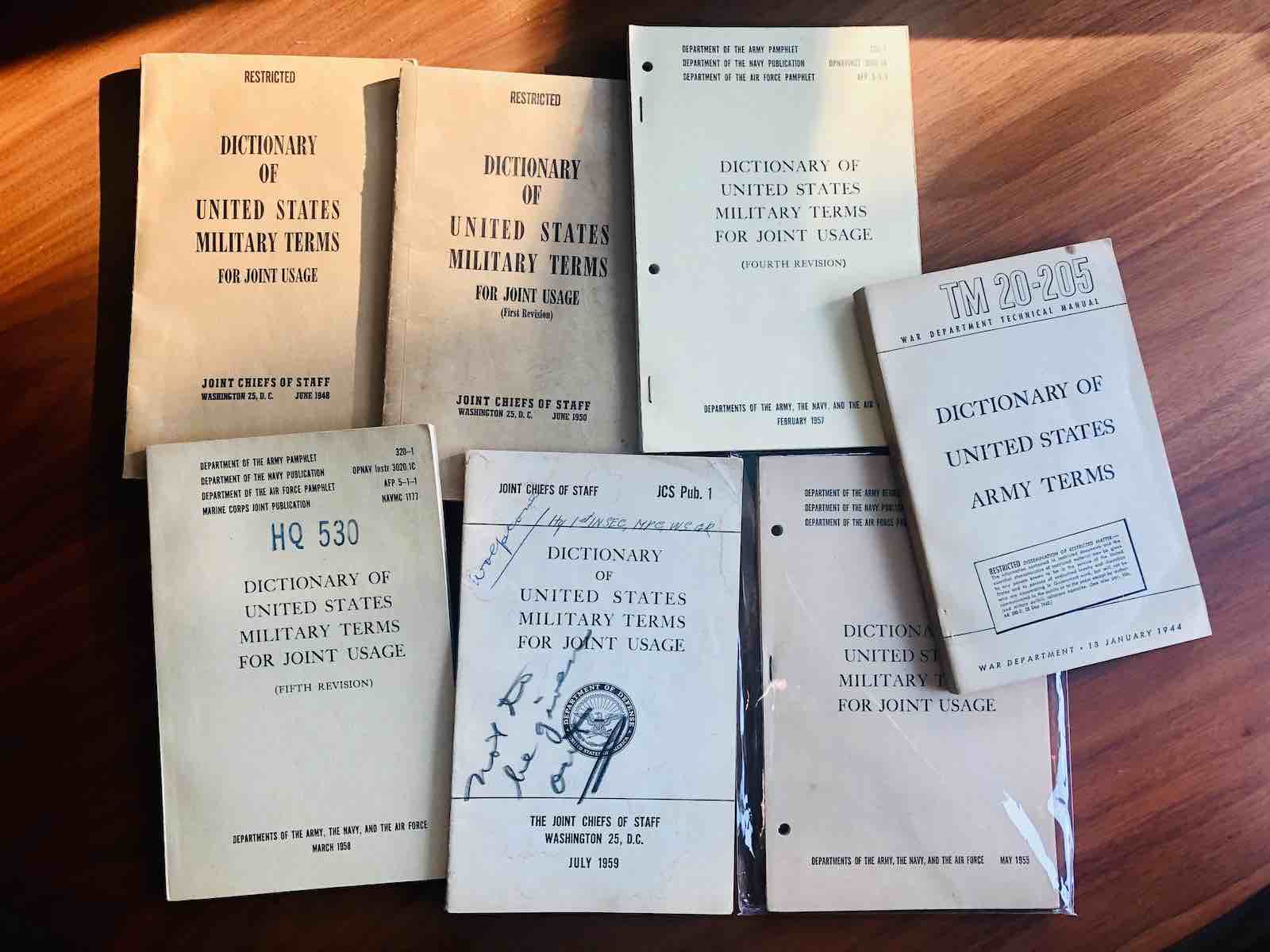

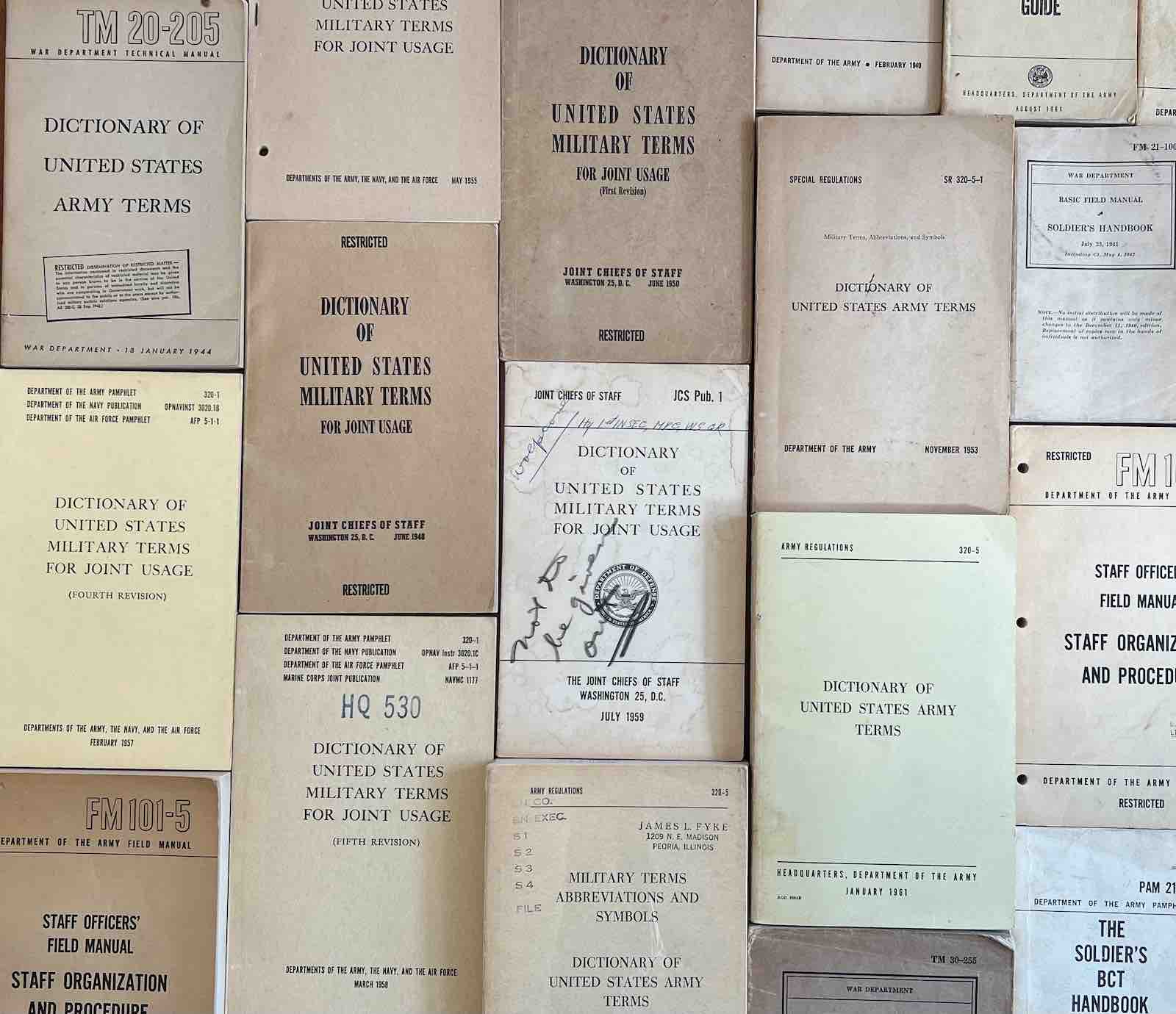

The first book I bought was a dictionary published by the Department of Defense in 1948. Between undergrad and graduate school, I worked for the U.S. military for a year. I was so confused by all of the jargon that I started looking for anything that could help me understand my colleagues and I started downloading online military dictionaries. This is what inspired this collection and my research. After I started graduate school, I bought my first dictionary while I was trying to figure out how much Army jargon existed. The 1948 dictionary is the first published by the new Department of Defense, preceded only by the Army’s first dictionary from 1944, which I purchased off of eBay soon after.

How about the most recent book?

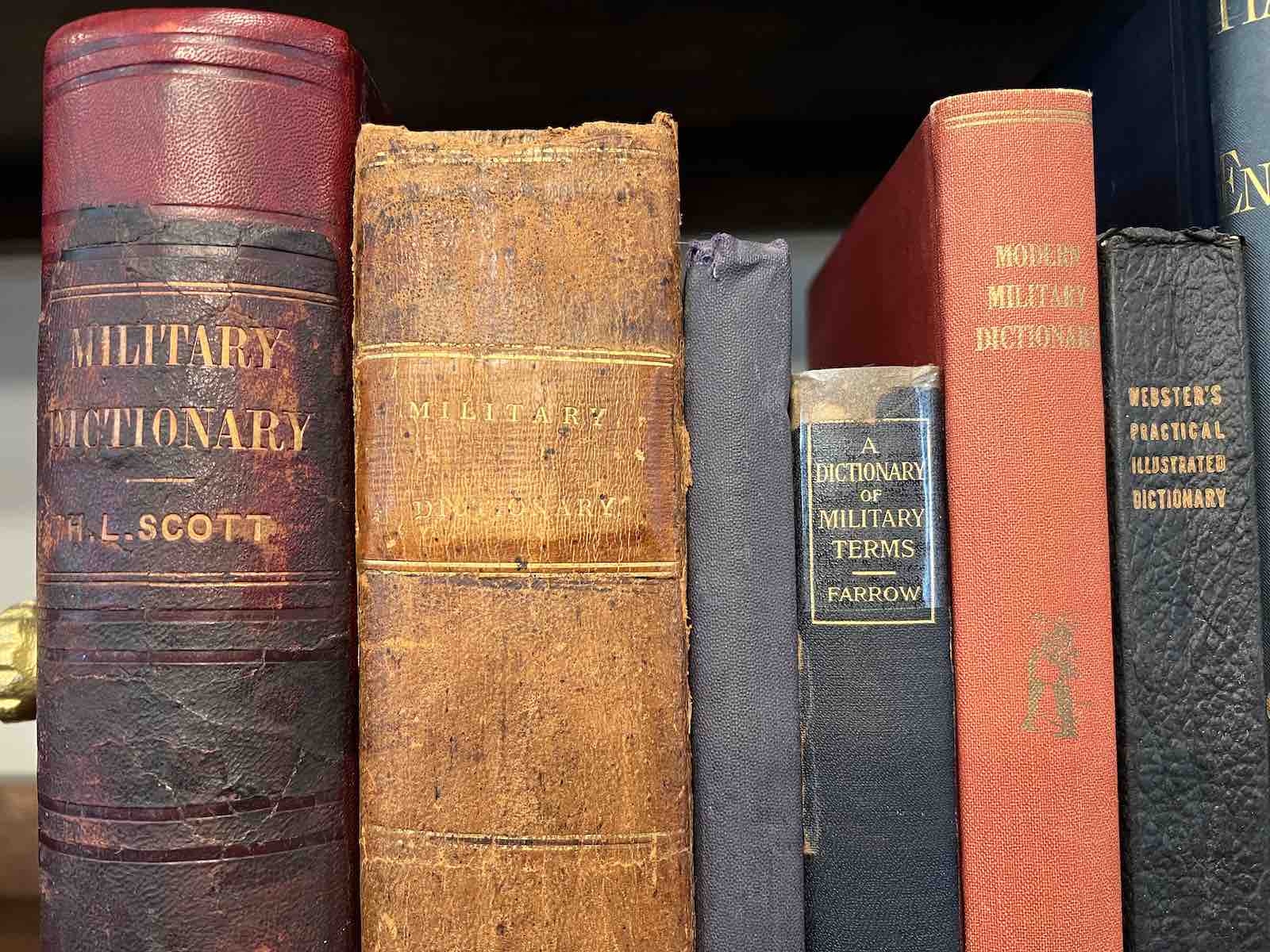

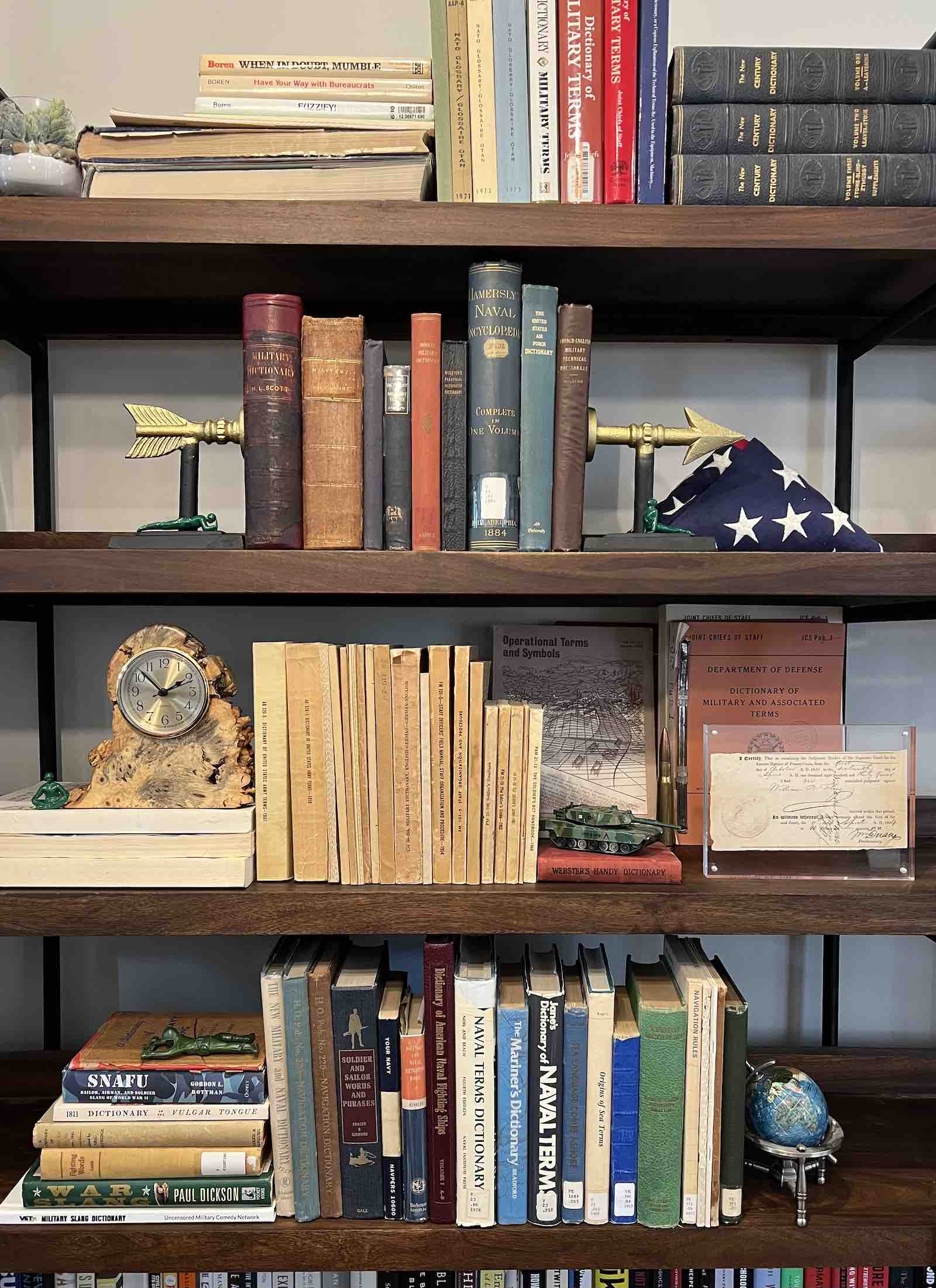

After my collection won the Honey & Wax Book Collecting Award, I used part of the prize money to purchase a work that was on my wish list – a military encyclopedia from 1885, compiled by Henry Farrow. Farrow was a tactics instructor at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point and he didn’t think that cadets and soldiers had the resources they needed to learn how to fight. He had a vision of creating a “military library,” so he compiled a dictionary, an encyclopedia, and several tactics publications. His encyclopedia is a treasure trove: three volumes, several thousand pages, but my favorite feature is that it is fully illustrated. There is a lot of obscure archaic military terminology that is very hard to interpret or understand. Many of those terms are illustrated in Farrow’s encyclopedia, giving me a great resource for understanding the rest of my collection. It has everything from fortification blueprints, to recipes, to the curriculum for training various types of officers, to deep discussions of famous American battles.

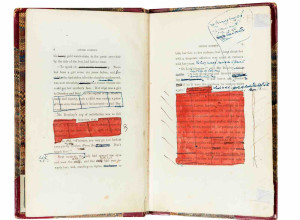

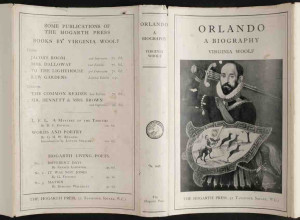

And your favorite book in your collection?

My favorite book is a first edition of William Duane’s dictionary from 1810. It is the oldest military dictionary that I have found that was fully compiled and published in the United States. This was one of the early dictionaries that I purchased and I spent a great deal of time researching the author, the signatures and doodles in the dictionary, and the ephemera: I found a court document signed by William Duane himself tucked into this book. This was the book that inspired me to research the stories of the books themselves, not only their contents. To figure out the story of this particular book, I had to decipher handwriting, search cabinetmakers records and property sales in Philadelphia, find gravestones, work with Independence National Park archivists, and map forts in Maine to figure out what the owner had doodled in the back cover. That was one of the most fun research questions I have ever pursued and it taught me a great deal about how to do historical research.

Best bargain you’ve found?

Honestly, a good portion of my collection was purchased on eBay. Most often, my finds were from estate sales or folks cleaning out their parents or grandparent’s garages, where they found a few old military manuals mixed in among uniforms. While the oldest dictionaries I have are quite valuable, most military manuals from the last century do not have much, or really any, resale value. For example, the market for military dictionaries from the 1950s is not terribly lively (I wouldn’t be surprised if I were personally the entire market) so I’ve been able to purchase dictionaries from that decade for as little as $3.

I started collecting dictionaries in order to complete my doctoral research because no single archive has all of the U.S. military’s dictionaries. Even more challenging, less than half of my collection has ever been digitized. As a student, I wasn’t able to purchase the most expensive books, so I was always bargain hunting. Sellers often gave me discounts when I told them about my collection and my research. My friends would also keep an eye out for military dictionaries when they went to used book stores and often there were great finds. My friend spotted Henry Farrow’s military dictionary from 1915 and a Naval encyclopedia from 1884 in a used bookstore in D.C. and she snagged them for me.

How about The One that Got Away?

In general, the online military dictionary inventory doesn’t turn over very quickly, so for me, the ones that got away are still available but are rare and expensive, and a bit outside of the bounds of my collection. Most of them are older British Navy or maritime dictionaries, like William Falconer’s Universal Dictionary of the Marine. The U.S. military inherited a great deal of its language from the British military, so I would love a chance to see Falconer’s dictionary in person. Every now and again, I’ll browse historical standard English dictionaries – like an original Johnson, Webster, Bailey, or Calepino. I was able to spend a long afternoon in the Grolier Club when they had Bryan Garner and Jack Lynch’s exhibit of historical American dictionaries. I am grateful that I had the chance to enjoy others’ collections and for now, I’ll keep relying on eBay.

What would be the Holy Grail for your collection?

My Holy Grail is the original NATO glossary. It is a French-English military dictionary that was published by the alliance sometime in the early 1950s. NATO started publishing official glossaries after finding that the alliance had dozens of internal glossaries that differed and even contradicted one another. I have collected almost all of the NATO glossaries except for the first two. I’ve interviewed dozens of people for my academic work on military language (including a historian at NATO), and so far, no one has ever seen a copy of the first glossary. In the 1950s, NATO policy was to destroy obsolete dictionaries, so that is likely why the original is so hard to find. I remain optimistic that one still exists somewhere.

Who is your favorite bookseller / bookstore?

It is hard to choose a favorite because I haven’t met a bookstore I didn’t like. In Washington D.C., my local favorite is Capitol Hill Books, and I also visit Politics and Prose, Kramer’s, and Second Story Books. Whenever my husband and I travel, we always end up in a bookstore. (And he always happily scans the shelves for dictionaries.)

I was lucky to grow up in a household full of books and bookstores were a part of my childhood. One of my earliest memories is walking into a bookstore in Ithaca with my dad, negotiating how many books I should be allowed to get. We would visit Buffalo Street Books, Borders, and Barnes & Noble and I would argue for as many books as possible. In a way, I’ve been collecting books for almost my entire life.

What would you collect if you didn’t collect books?

![]() I am pretty minimalist about most things, other than military dictionaries and science fiction. Besides books, I love paper goods of all kinds. Notebooks, notepads, cards, beautiful wrapping papers and cocktail napkins. I like to collect things that I can use or gift.

I am pretty minimalist about most things, other than military dictionaries and science fiction. Besides books, I love paper goods of all kinds. Notebooks, notepads, cards, beautiful wrapping papers and cocktail napkins. I like to collect things that I can use or gift.