Nate Pedersen on The Books of Pseuoscience

The cover of Pseudoscience: An Amusing History of Crackpot Ideas and Why We Love Them

Pseudoscience: An Amusing History of Crackpot Ideas and Why We Love Them is a rollicking visual and narrative history of popular ideas, phenomena, and widely held beliefs disproven by science. It's my third nonfiction book, involved a lot of research and a bit of book collecting, and came out in February from Workman/Hachette.

The Bermuda Triangle. Personality tests. Ghost hunting. Crop circles. Mayan Doomsday. These crowning achievements of pseudoscience, and many more topics, are covered in its pages. Pseudoscience is also the third book I’ve co-written with Dr. Lydia Kang, after Quackery: A Brief History of the Worst Ways to Cure Everything (2017) and Patient Zero: A Curious History of the World’s Worst Diseases (2021).

While researching the book I also enjoyed collecting (or, at least, thinking about collecting) some titles from the deep waters of pseudoscience. Here are a few of my favorites:

1. Manlife (1923) by Alfred Lawson.

Lawson was a first-rate crackpot and shameless self-promoter. After developing a comprehensive pseudoscientific philosophy that he dubbed 'Lawsonomy' after himself, and then building a University in Iowa to disseminate his ideas, he settled in to serve as the University’s 'Supreme Head and Knowledgian'. In a lifetime spent self-publishing his theories, Lawson’s standout collection of essays is Manlife, which was published by his own Humanity Publishing Company in 1923.

My favorite part about the book is the introduction, clearly written under a pseudonym by Lawson himself. A direct quote from the introduction sums it all up: “…to try to write a sketch of the life and works of Alfred W. Lawson in a few pages is like trying to restrict space itself. It cannot be done.” Copies start at $15 online.

2. The Old Straight Track (1925) by Alfred Watkins

This is a hard book to find in the original edition without spending a small fortune ($750 for a first edition). I had to settle for a later reprint. Watkin’s pseudoscientific masterpiece, however, became the urtext for the ley lines movement, an idea that the British landscape is riddled with straight alignments (“leys”) between ancient landmarks and monuments believed to hold sacred power. These leys, the theory goes, supposedly generated sacred energy or provided a landing grid for visiting UFOs.

It’s a little silly, but it’s also relatively harmless. As someone who enjoys a good countryside quest myself, Watkins’ book entertained me, and I gradually grew appreciative of his imaginative enthusiasm for the ancient history and archaeology of England.

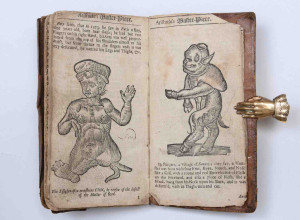

3. Glazial Kosmogonie (Glacial Cosmogony) (1912) by Hans Hörbiger

This German masterpiece of pseudoscience was impossible for me to find (none were available anywhere online) so I had to rely on secondary sources as I wrote the chapter on the super bizarre Nazi cosmological theory called 'World Ice. The basic tenant is that the stars you see in the night sky are not actually stars… they are frozen bits of ice from a water-logged star that exploded in the sky a really long time ago. Oh, and the moon is the fourth moon we’ve had in a long series of them.

This theory, which found a shocking amount of traction in Nazi Germany, was headed by Hans Hörbiger, an engineer and (very) amateur astronomer who wrote this doorstop of a book that weighs in at 712 pages in double columns in 1912. One of my secondary sources described it brilliantly: “[it is filled] with photographs and elaborate diagrams, heavy with the thoroughness of German scholarship from beginning to end, [and] totally without value. It is almost as though the Germans, so superior in most fields of scientific learning, refused to be surpassed even in the field of pseudoscience.”

4. The Bermuda Triangle (1974) by Charles Berlitz

This is the seminal text that popularized the concept of the Bermuda Triangle as a haunted stretch of ocean. Copies are easy to track down (it sold 20 million copies after all) and it’s a necessary reference for the explosion of interest in the Bermuda Triangle during the 1970s. Bertliz’s book, full of questionable conclusions, also makes compelling reading for a reason - he knew how to build a mystery. Copies are available online for less than $5.

5. Bleak House (serialized between 1852 and 1853) by Charles Dickens

Charles Dickens’ classic novel about an extended legal case in Victorian England was not the first book I imagined necessary for my pseudoscience research library. However, Bleak House also happens to contain with its pages a vivid portrayal of Dickens’ pet pseudoscientific interest, spontaneous human combustion. A minor character in the book, the alcoholic rag dealer Mr. Krook, exits from its pages after meeting an untimely, and fiery, end.

The Victorian literary critic George Lewes took umbrage with Dickens’ use of spontaneous human combustion as a plot device and took to the press to air his complaints. Dickens leapt to his own defense, adding a preface to the next serial installment defending his use of spontaneous human combustion, and included commentary on it in the final edition of the novel. While Bleak House itself is easily acquired, I didn’t have it in my budget to acquire the original serial edition ($4,500+) or the first edition of the final published novel ($1,200+) interesting as they would have been.

All of these titles, along with many others, feature in my new book, available wherever books are sold with signed copies from The Book Lady Bookstore in Savannah, Georgia.

This is a guest post for Fine Books & Collections by Nate Pedersen who contributes our regular Bright Young Booksellers, Bright Young Collectors, and Bright Young Librarians columns