Medieval Women and the Written Word

The British Library is using books, documents, and other objects to recover the lives and voices of women in the Middle Ages

When researching potential items to include in the British Library’s current exhibition Medieval Women: In Their Own Words (on view through March 2, 2025), I was struck by the exceptional importance of books and documents for recovering women’s histories. While many surviving artifacts from the Middle Ages were probably made and used by women, establishing this can be challenging. Books, on the other hand, can speak.

As written works, they often tell us a great deal about the people who shaped and interacted with them, and frequently these were women. They reveal women authors, letter writers, users, scribes, and printers, to name but a few. The exhibition seeks to uncover the varied lives of women across society, yet it is also an exploration of the close relationship between medieval women and written culture.

Women Writers, Lost and Found

In the Middle Ages, women authors were greatly outnumbered by male authors, largely because, among other inequalities, girls were rarely educated to the same level as boys. Nevertheless, works by female authors survive in a wide range of genres, often voicing distinctly female perspectives. Those on display in Medieval Women include works by Christine de Pizan (d. 1430), the first professional woman author in Europe, who disputed conventional representations of women in male-authored literature; Hildegard of Bingen (d. 1179), a polymath and abbess, who described her ideas about God through feminized imagery; Gwerful Mechain (d. 1502), a Welsh poet who celebrated female sexuality in her rollicking “Poem on the Vagina”; and Ḥafṣa bint al-Ḥājj ar-Rakūniyya (d. 1190/1), a poet from Granada who wrote in Arabic and countered the effusive sentiments of her lover Abū Jaʿfar with coolheaded reserve.

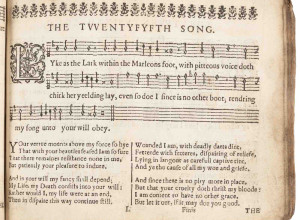

In fact, there were probably more medieval women authors than we realize owing to the combined effects of religious censorship and anonymity. It is sobering to think how close we came to losing the works of English mystics Julian of Norwich (d. c. 1416) and Margery Kempe (d. c. 1438). Julian of Norwich wrote two versions of her Revelations of Divine Love, the first known female-authored work in the English language. The “Short Version” survives in just one medieval copy, while the “Long Version” survives only in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century copies made by exiled English nuns in France (probably from a single now-lost medieval manuscript). The Book of Margery Kempe, the first autobiography in English, survives in just one manuscript, which was discovered in 1934 (allegedly while the owners of a country house were searching for ping-pong balls). Up to that point, it was known only from a series of extracts, stripped of Margery’s voice and biographical details, that were published in the early sixteenth century. Widespread suspicion of women’s writings and centuries of religious upheaval were nearly enough to obliterate these important works. How many more medieval women’s writings have we lost entirely?

Visions and Valentine’s

Most extant documents from the Middle Ages contain more formal types of texts. Personal correspondence, especially that of women, rarely survives. The Paston Letters, an unparalleled cache of over 1,000 letters belonging to a fifteenth-century Norfolk gentry family, give a rare, intimate view into family life. They reveal women juggling the demands of domestic life and social advancement, from shopping lists and love matches to armed skirmishes against rival families. They also include the first surviving Valentine’s letter in English, sent by Margery Brews to her “right worshipful and well-beloved Valentine” John Paston in February 1477.

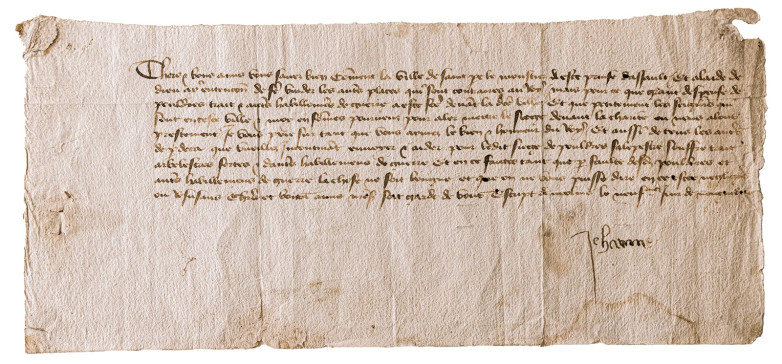

Joan of Arc, perhaps the most famous woman from the Middle Ages, is vivid in the popular imagination in part because her defiant words are preserved in the records of her heresy trial, after which she was burned at the stake in 1431. A letter from earlier in her short but brilliant career as a spiritual visionary and military leader is on display in the UK for the first time as part of this exhibition, on loan from the Archives municipales de Riom. Joan sent the letter to the citizens of Riom, France, on November 9, 1429, entreating the city to send military supplies. As she was illiterate, Joan dictated her letter to a scribe but signed her name, “Jehanne,” at the end. Little connects us more powerfully to a historical person than seeing their signature, the authentic mark of their presence in the world.

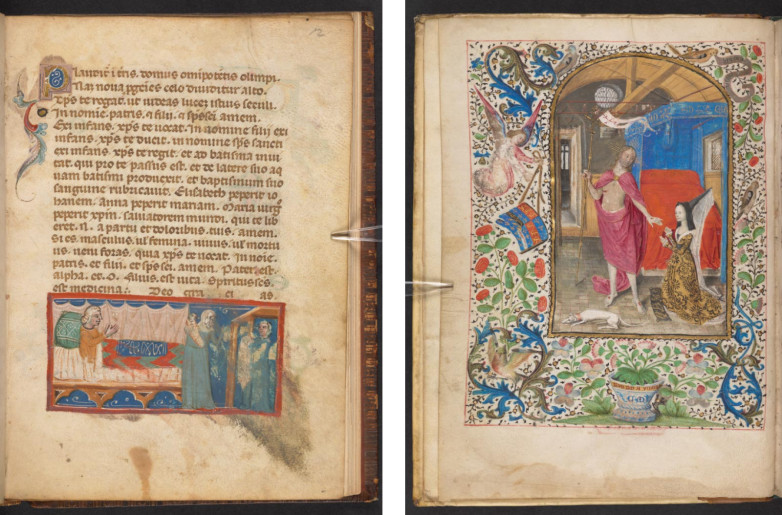

We can see women’s influence in book culture even when their own words do not survive. Over the course of the Middle Ages, rates of book ownership increased dramatically, and women are recognized as key drivers of this change. Elite women often patronized literature; for example, Margaret of York (d. 1503), Duchess of Burgundy, commissioned the first book printed in English, Caxton’s Recuyell of the Histories of Troye (1473). The exhibition includes a personalized treatise that Margaret commissioned from her almoner (or alms distributor), Nicolas Finet. It takes the form of a dialogue between Margaret and Christ, as illustrated in the beautiful frontispiece, which shows them conversing in her bedroom.

Traces on the Pages

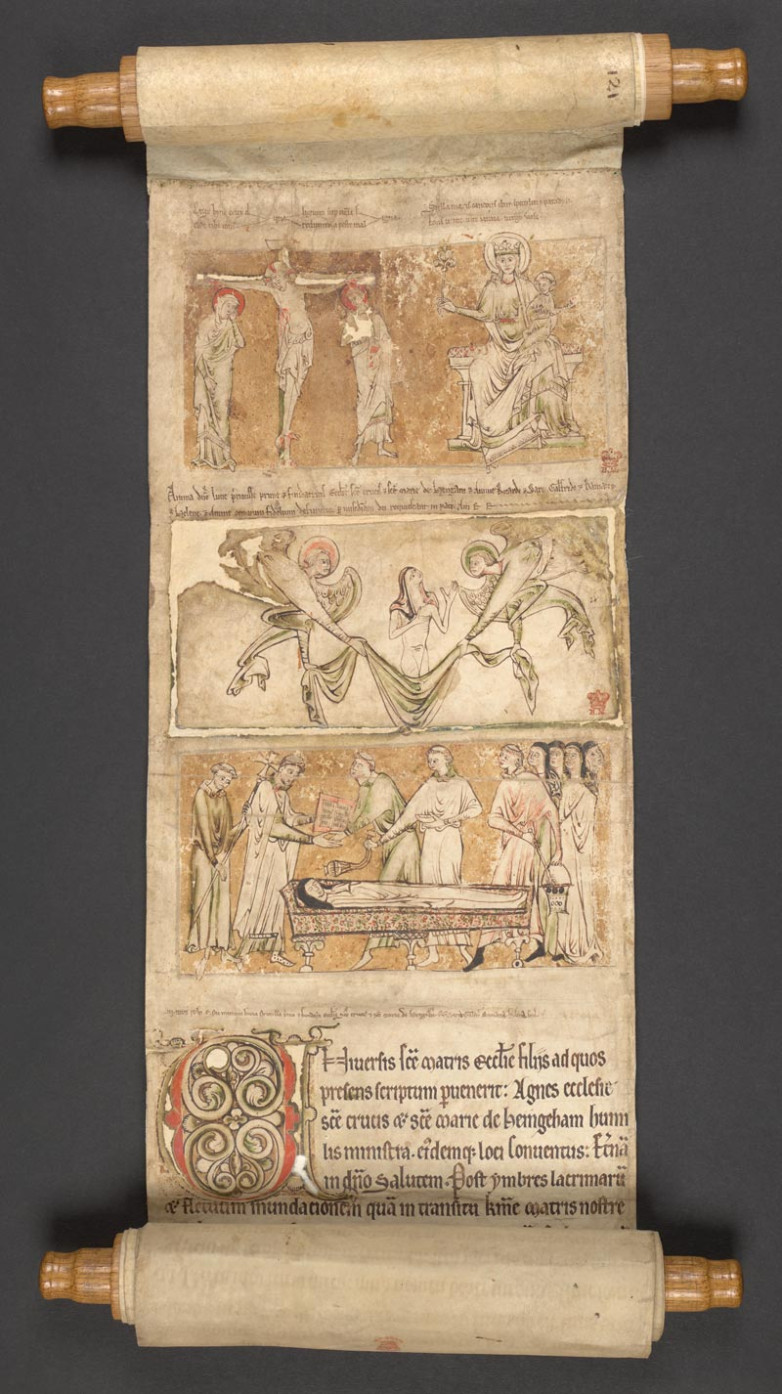

Some of the most poignant traces of women in books reveal their physical touch. According to medieval belief, manuscripts containing the Passion (or life story) of St. Margaret, patron saint of pregnancy and childbirth, were effective amulets for women giving birth. A copy of the Passion of St Margaret made in fourteenth-century Padua ends with a childbirth prayer beginning “Exi infans Christus te vocat” (Come forth infant, Christ summons you). This is accompanied by a picture of a birthing scene that has been moistened and smudged, probably by the devotional kissing of women hoping for a safe birth.

Book production was another area in which women were active. A majestic gradual (choir book for the Mass) from the Cistercian Abbey of Seligenthal, Germany, contains inscriptions stating that a thirteenth-century nun named Elisabeth first wrote the manuscript, and that a later nun, Elisabeth Hüttlen, choir mistress of the convent for thirty-five years, added extra material to it in 1462. As well as demonstrating these women’s scribal and musical skills, the inscriptions suggest that the manuscript was in use at the abbey for at least 200 years.

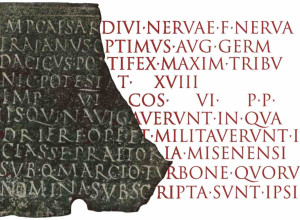

The introduction of movable type printing to Europe in the fifteenth century created opportunities for women in the printing industry. Most, however, worked anonymously in family workshops, and their contributions are generally invisible. The first woman in Europe to print a book under her own name was Estellina Conat, a Jewish woman in Mantua, Italy, in the 1470s. Estellina printed the first edition of Jedaiah Ben Abraham Bedersi’s Beḥinat ha-‘Olam (The Contemplation of the World), a Hebrew poem written after the expulsion of Jews from France in 1306. The colophon, or printer’s statement at the end of the book, declares: “I, Estellina, the wife of my worthy husband Abraham Conat, wrote [i.e. printed] this book.” She used the word “katavti” (wrote) because no Hebrew term for printing existed yet.

The British Library is fortunate to be one of the world’s great repositories of words. In curating the exhibition, we were keen to use as many different sources as possible to recover the lives of medieval women. While books and documents are not the only items on display—there is, for example, furniture, jewelry, and even a lion’s skull—we hope that visitors will be as excited as we were to discover that medieval books have such vital and little-known stories to tell.