The Book of Esther in the Age of Rembrandt exhibition, now at the Jewish Museum in New York through August 10, explores how different artists, patrons, and cultures fashioned Queen Esther in the seventeenth-century Netherlands and shaped her into a woman for their time and in their image—seen through paintings, prints, drawings, Jewish ceremonial art, decorative objects for the home, and theatrical plays. The exhibition is co-organized by the Jewish Museum and the North Carolina Museum of Art in Raleigh. Following its New York showing, it will travel to North Carolina in September 2025, and a condensed version will be presented at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston, opening in August 2026.

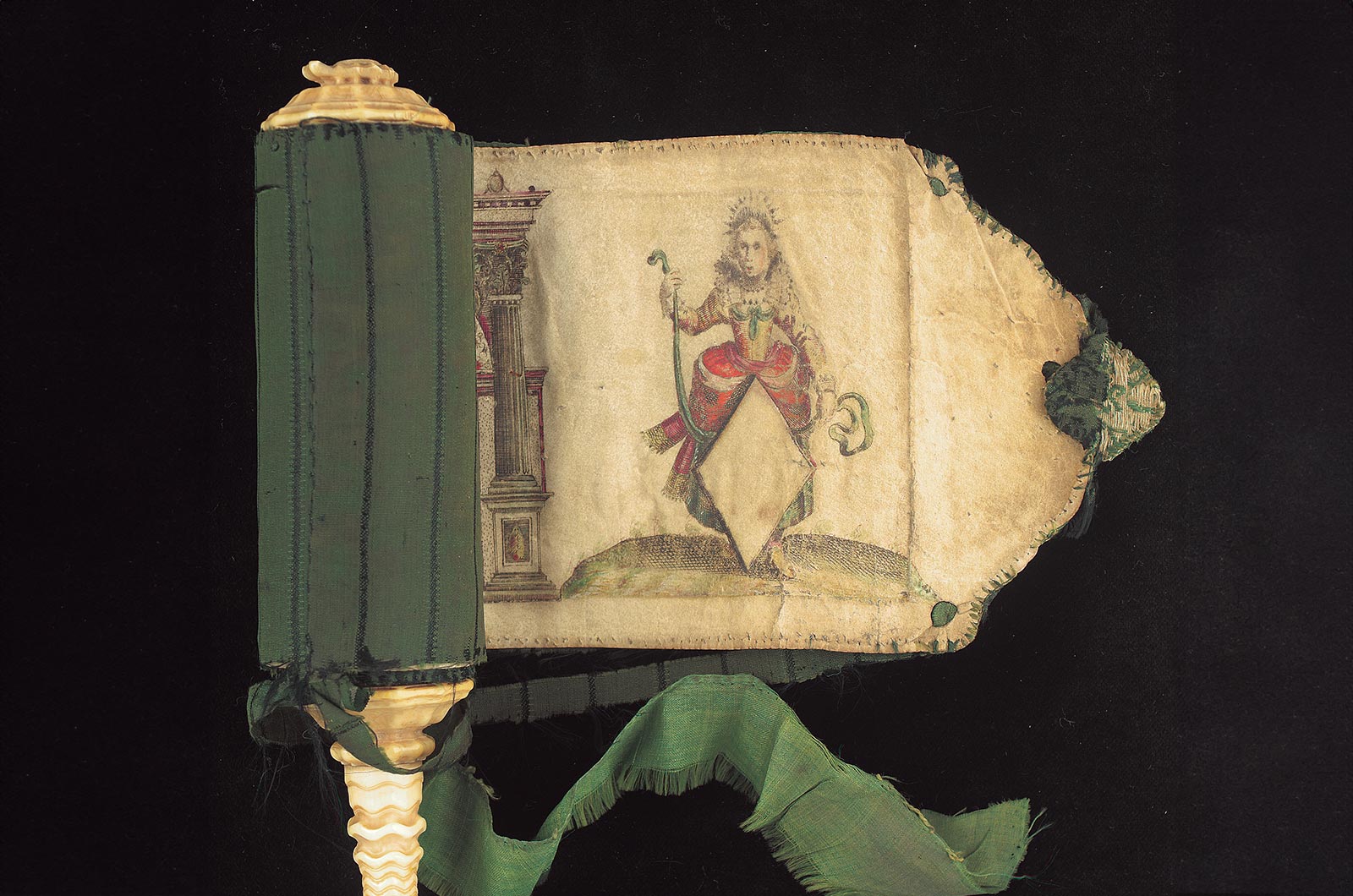

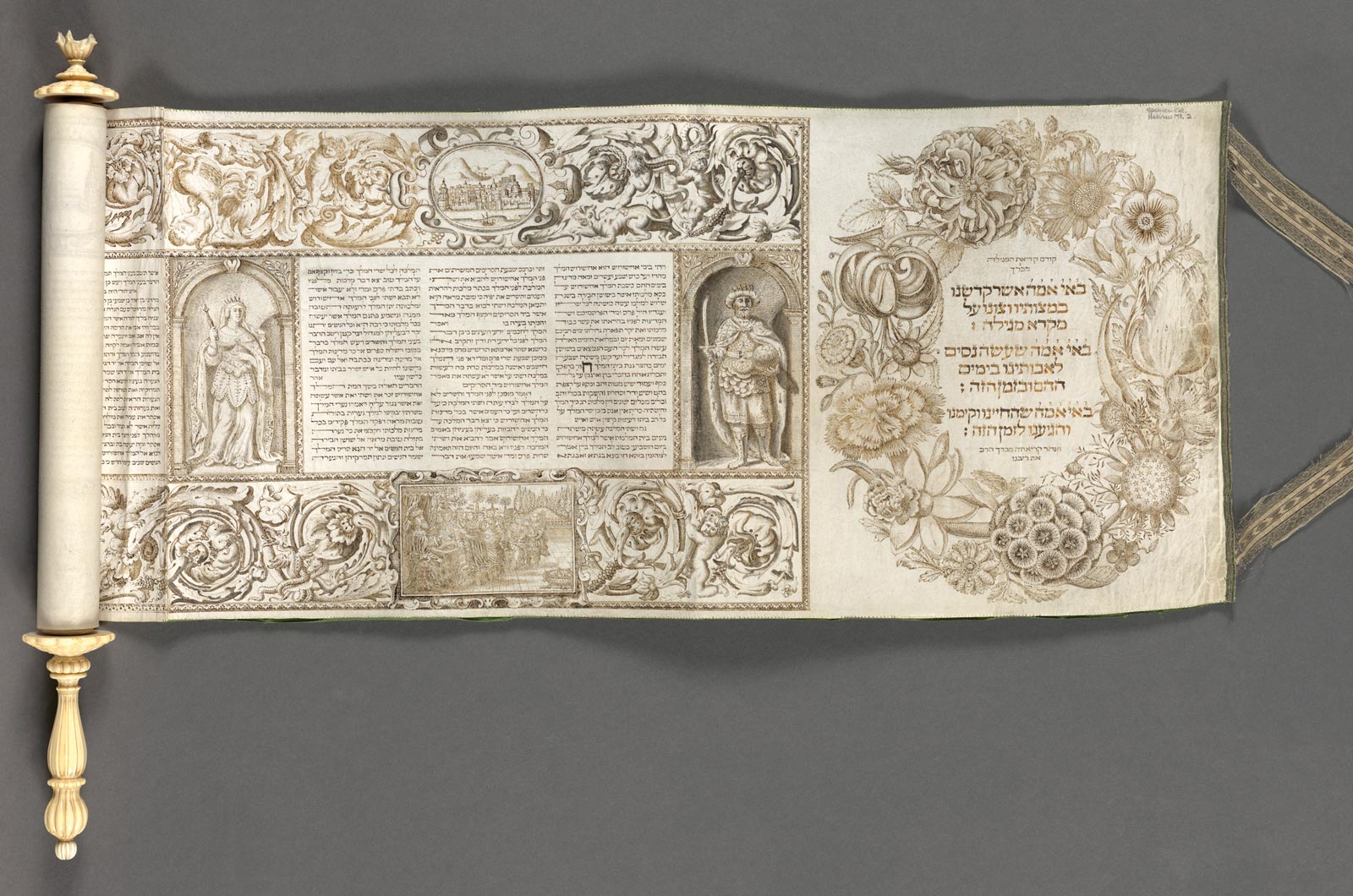

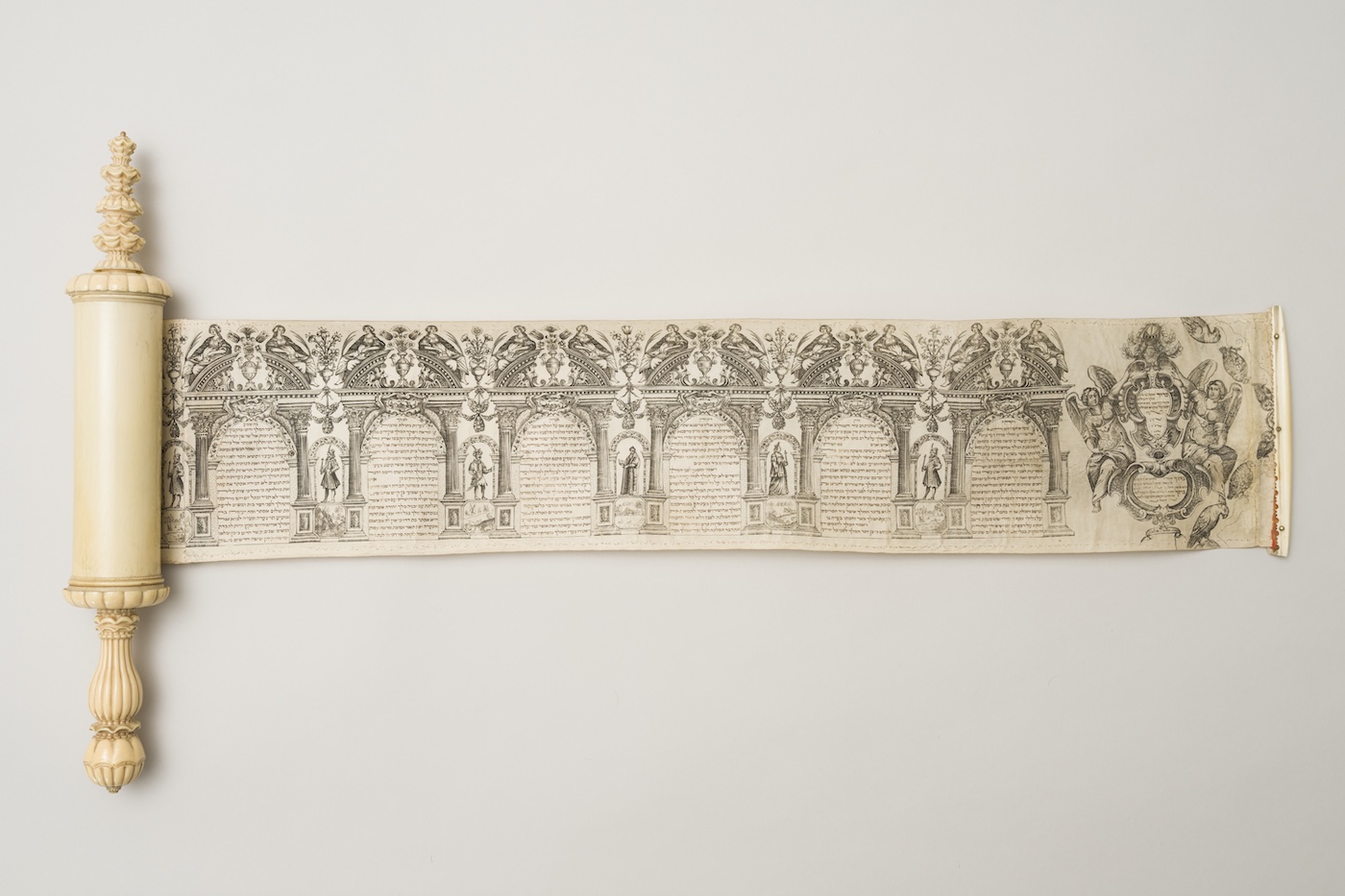

As this exhibition illuminates, for Rembrandt’s time and his seventeenth-century Dutch audience, Queen Esther was especially popular as a beautiful and courageous woman, a model of virtue and a symbol of bravery for the Dutch in their fight against the Spanish monarchy—the most powerful one at the time. For the Dutch, Esther had “street smarts,” intuition, and diplomacy; she knew what to do to save her people and when to speak and act. For the Spanish and Portuguese Jewish community, Esther was not unlike their own ancestors and families, forced to hide their Jewish identity for fear of being persecuted. She offered a glimmer of hope and salvation. Jewish or Christian, Portuguese or Dutch, these artists, patrons, and audiences were primed to adopt and feature Esther as their own. In their midst, they had the magic of Rembrandt and his contemporaries as well as the innovation of Jewish engravers to visually bring to life the ancient biblical story of Queen Esther.

When I first started conceiving of this exhibition more than five years ago, I knew that the exhibition needed to create dialogues among objects from various faiths and cultures—to bring Jewish ceremonial art into conversation with the great Rembrandts, with the canon of Western art history. This concept was rooted in pairing an illustrated Esther scroll and a Rembrandt engraving to highlight their shared source of inspiration from the Hebrew Bible, and to explore how different communities, Jewish and Christian, found common ground in Queen Esther as a heroine for their time. It was also about presenting how Jewish ceremonial art more broadly was not made in and did not exist in a vacuum, divorced from the art and culture of the period. Rather, like Dutch art, Jewish ritual art responded to its environment, and cultural exchange naturally arose.

Strikingly multicultural, the Netherlands, and specifically Amsterdam in Rembrandt’s time, gave refuge to large numbers of immigrants, including Sephardic Jews whose families had been forced to convert to Catholicism in Spain and Portugal (called conversos), as well as Ashkenazic Jews from Central and Eastern Europe. Christian immigrants from Northern and Central Europe and the British Isles also settled in Amsterdam, fleeing religious persecution, searching for economic opportunities, or relocating after being displaced by war. Most of them settled in Vlooienburg, a man-made island in the eastern part of the city, which became the epicenter of Jewish life. Rembrandt, too, lived in the exceptionally diverse eastern part of Amsterdam together with many of the city’s Jewish immigrants, Christians, and a small free Black community.