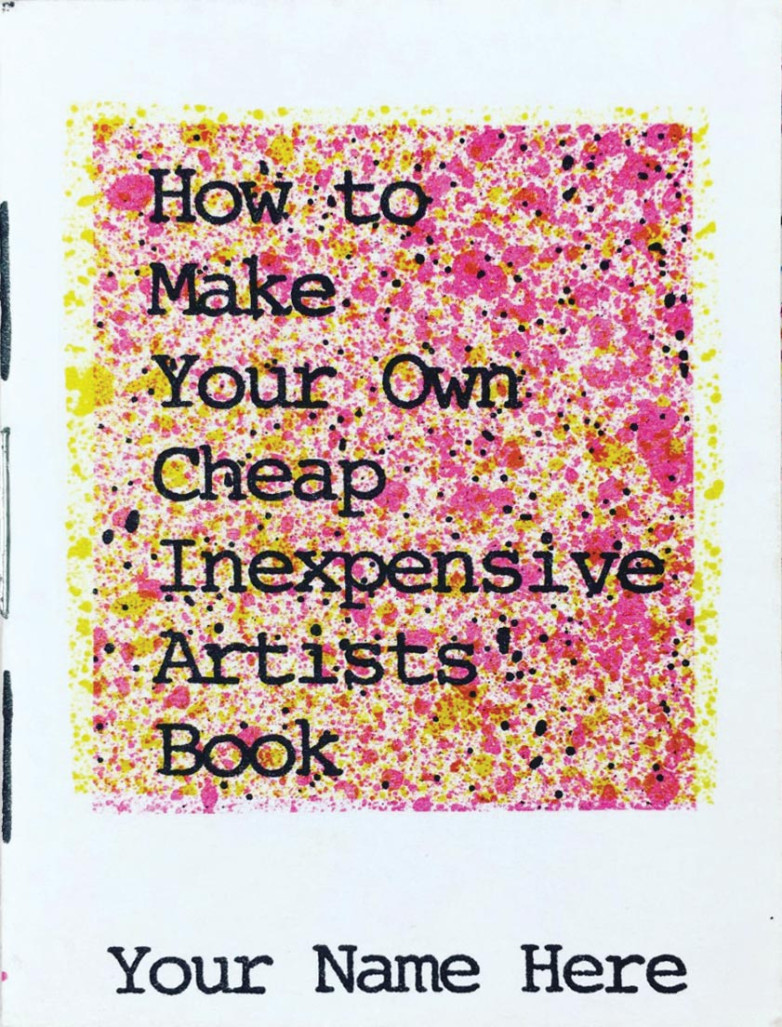

Vanderlip wrote just two short paragraphs for her catalogue and commissioned two longer essays. As a curatorial strategy for selecting publications for the exhibition, she utilized the Duchampian prompt: if the artist said their publication was an artist’s book, she accepted their designation.2 In addition, she excluded exhibition catalogues and artist portfolios.3 With her deference to artist-defined publications and just two self-imposed curatorial limits, she sidestepped the opportunity to further define what artists’ books were or could be, leaving this task to future curators and critics.

In the thirty years following her exhibition, there was a lively discussion about what artists’ books should be defined as. Many people—artists, designers, photographers, printers, critics, collectors—quickly tired of these ongoing discussions to refine the definition of artists’ books. Instead, there was a concentrated effort to shift the conversations to why and how publications were artists’ books, with less focus on “what is an artist’s book.” At the apex of these debates, Duncan Chappell published “Typologising Artists’ Books” in Art Libraries Journal in 2003, highlighting many definitions that had evolved over time.

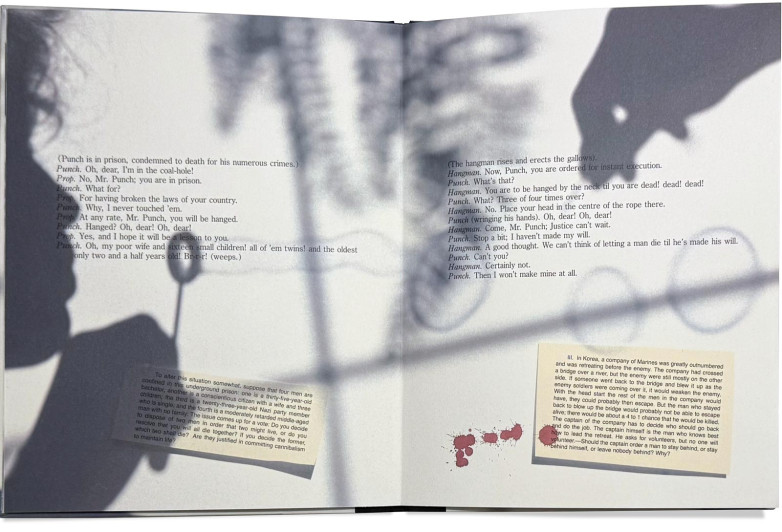

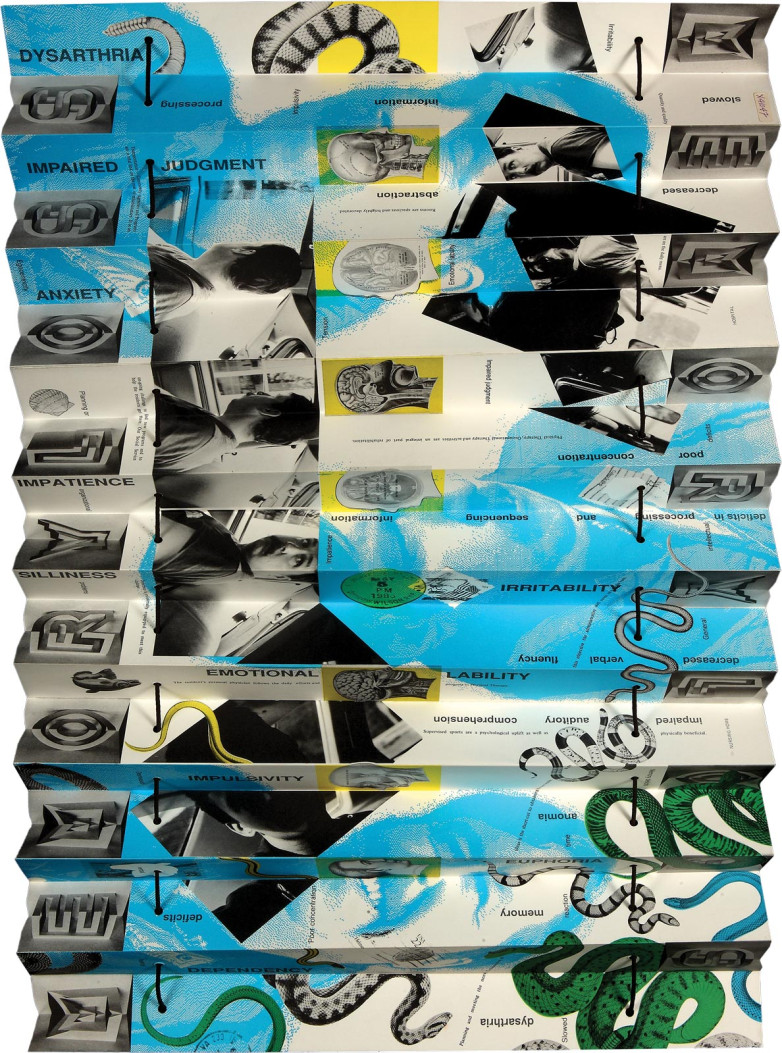

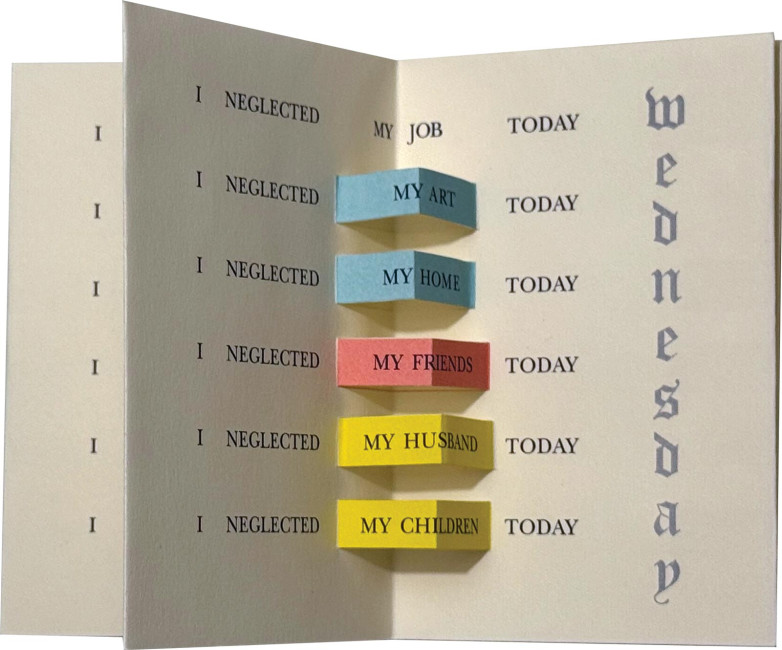

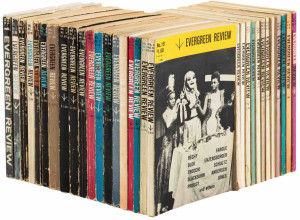

The most influential antecedents of post-1973 artists’ books can be found among conceptual photobooks and FLUXUS publications. Ironically, the most influential conceptual photobook artist, who started publishing in 1962, Ed Ruscha, has quietly distanced himself and his “little photobooks”4 from the genre of artists’ books. Artists involved with FLUXUS utilized creative publication formats often to document performances or as instructions to activate performances. Both strategies used by 1960s conceptual photobook artists and FLUXUS artists found that artist publications were a critical expression, both creative and documentary. In the latter years of the 1960s and into the ’70s, there was a shift to incorporate a greater diversity of artists who were bringing social justice narratives to artists’ books publications. This was a time of anti-establishment political and social movements, of experimental ideas and actions, in which artists were seeking to get art off the wall and into the hands of the viewer. Not only with happenings and performance art, but also with mail art, Pop art, conceptual art, and minimalist movements, where concept was more important than its realization, and where there was a shift from art as an object to art as an idea.